Understanding Malaria Transmission: The Role of Mosquitoes

While considered rare within the United States today, malaria can be extremely common in humid, hot climates and is one of the highest-occurring vector diseases worldwide.

Scroll to learn more about malaria, its transmission via mosquitoes, and methods for helping to curb its spread in your community via larviciding and other IMM strategies.

Catch an in-depth explanation of the parasite that causes malaria, its bite and infect transmission cycle via mosquitoes, and more in this webinar snippet.

To stay up-to-date on mosquito transmission in Florida, subscribe to Dr. Day’s newsletter here.

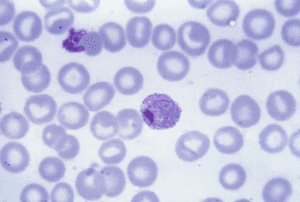

Malaria is caused by infection of red blood cells with protozoan parasites belonging to the Plasmodium genus, with five species being primarily responsible for human infections: Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium malariae, Plasmodium ovale, and Plasmodium knowlesi. Each species exhibits distinct characteristics, geographic distribution, and severity of the disease they cause.

Malaria is caused by infection of red blood cells with protozoan parasites belonging to the Plasmodium genus, with five species being primarily responsible for human infections: Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium malariae, Plasmodium ovale, and Plasmodium knowlesi. Each species exhibits distinct characteristics, geographic distribution, and severity of the disease they cause.

Up to this point, all malaria cases identified within Florida have been caused by the plasmodium vivax species – widely distributed globally but particularly noted for its spread of malaria in Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. While generally less severe than P. falciparum infections, the most prevalent cause of malaria in Africa that accounts for the majority of malaria-related deaths worldwide, P. vivax is known for its ability to remain dormant in the liver for extended periods, causing relapses of the disease months or even years after the initial infection.

Understanding the malaria parasite’s life cycle is crucial to comprehending its transmission and identifying potential intervention points to combat it.

Malarial transmission requires two factors – a female Anopheles mosquito and a human host – and what is known as the “bite and infect” mechanism.

Malarial transmission requires two factors – a female Anopheles mosquito and a human host – and what is known as the “bite and infect” mechanism.

The life cycle begins when a female Anopheles mosquito, the vector, takes a blood meal from an infected human. While taking a blood meal, the mosquito also ingests the malaria parasite – in this case, P. vivax – from the infected human’s bloodstream.

Inside the mosquito’s midgut, the malaria parasite undergoes sexual reproduction and develops into sporozoites, the infective form of the parasite. This process can take eight to fifteen days, over which the mosquito must survive. These sporozoites then migrate to and infect the mosquito’s salivary glands. The mosquito is now considered infected and primed to vector the malarial parasite when it bites and injects the sporozoites into another human host’s bloodstream.

At this point, the sporozoites travel to the human’s liver, mature, form merozoites, and travel into the bloodstream, infecting and destroying red blood cells and triggering the characteristic symptoms of malaria – fever, chills, anemia, and organ failure.

Most mosquito species are not able to transmit malaria. Even in the case of anopheles, a mosquito known for its ability to vector malaria, not all species are able to as some do not feed on humans, are not susceptible to human malaria parasites, or have too short of lifespans for the parasite to fully mature.

Most mosquito species are not able to transmit malaria. Even in the case of anopheles, a mosquito known for its ability to vector malaria, not all species are able to as some do not feed on humans, are not susceptible to human malaria parasites, or have too short of lifespans for the parasite to fully mature.

Still, certain anopheles species are uniquely adapted to transmit malaria to humans due to their feeding habits, favorable habitats for breeding larvae and maturing into biting, flying adults and susceptibility to the Plasmodium parasites:

The EPA recommends an integrated mosquito management approach, which takes a holistic approach to mosquito control, including community education, surveillance, survey and mapping, larval control, and adult mosquito control.

The EPA recommends an integrated mosquito management approach, which takes a holistic approach to mosquito control, including community education, surveillance, survey and mapping, larval control, and adult mosquito control.

For areas that are more urban or developed, one of the best methods in particular to minimize the amount of mosquitoes is larviciding – utilizing product to target mosquitoes in their immature, larval phase, well before they emerge as flying, biting adults that can transmit infections.

Clarke’s Natular® G30 is an OMRI Listed, water-soluble mosquito larvicide formulation derived from a naturally-occurring soil bacterium (spinosad) that is effective on all four instars of larvae. It is proven to control twenty of the most common vector and nuisance mosquito species – including malaria-vectoring Anopheles – for up to 30 days.

Natular G30 is designed to kill mosquito larvae in bodies of water, and can be applied to dry areas before flooding as a pre-hatch tool. For applications by hand, ground, air, and drone, the G30 formulation is well-suited for common larval breeding sites such as:

Natular G30 is designed to kill mosquito larvae in bodies of water, and can be applied to dry areas before flooding as a pre-hatch tool. For applications by hand, ground, air, and drone, the G30 formulation is well-suited for common larval breeding sites such as:

Learn more about Natular G30 and the rest of the Natular larvicide portfolio here.